Features

Laura Gardner is an editor, lecturer and co-publisher of Mode and Mode. She holds a PhD from RMIT University, and her research and projects focus on the methodologies of experimental publishing and the performative and critical potential of the page in fashion and other creative fields. She lectures in the School of Fashion and Textiles at RMIT, as well as freelance writing and editing for fashion and art press. Recent writing includes: Viscose, Monument, 299 792 458 m/s, Press & Fold, Flash Art Online, among others. Talks and panels include Parsons Paris, ArtEZ, London College of Fashion (UAL), NGV Art Book Fair Symposium, RMIT Design Hub, and Lyonhousemuseum.

Experimental archives,

new fashion histories

The concept of the ‘archive’ seems to have captured once more the contemporary moment in fashion. Phrases like ‘archival fashion’ are circulating in fashion media like buzzwords: see, for instance, the prevalence of online luxury resale marketplaces; luxury boutiques adding ‘archival’ sections to their repertoire; brands newly investing in maintaining their archives in-house; and designers that continually speak of reconsidering the ‘archive’ in their design process. There is more access than ever before to fashion history, but has this fetishisation of fashion’s past—both as an aesthetic concept and as physical collections—commodified the archive?

For luxury brands, their archive—whether it be an actual maintained collection of the design house’s output, or a more abstract suggested history of the brand—has become an essential component in their company framework. Luxury fashion houses spend substantial budgets on the organisation and curation of their in-house archives for promotional activities as well as reference material for the design house’s ‘DNA’. For these companies, archiving their past is an expensive, but strategically necessary act. Creating and maintaining an archive services the brand and reinforces the boundaries of existing periodisations of fashion. Brands represent their archives in order to strengthen their own storied presence within the history of fashion.

Fashion is also periodised through museological institutions and, among other things, these exhibitions often too function as brand-building strategies. Major fashion exhibitions tend to be about still-operating fashion houses (for instance, Comme des Garçons, Alexander McQueen and Balenciaga), and are usually produced in close collaboration with the brands they portray. While the museologic reconsiderations of their houses undoubtedly have historical value, it also seems that these shows are brand-building opportunities. The production of fixed historical periods of fashion—more so, perhaps, than in other creative industries—is problematised by its preference to brands still on the current market.

In the context of these commercial dynamics in the archiving and representation of fashion, what can fashion archivists learn from recent movements in archiving more generally, particularly in the arts and humanities? The politics of archives, particularly in art and museological contexts, have transformed with widespread access to digital technology. Recent writing on archives and archival practice in art promotes the idea of the archive as something that functions ‘not as something static but a set of materials that would talk to one another and could constantly be reanimated and put into parallel conversations in order to produce new meaning and relationships.’ This is seen in digital archives, such as Ubuweb—which focuses on avant-garde and counter-cultural music, poetry, literature and art—that challenge traditional notions of the archive and the knowledge they make available by ‘[proposing] a different sort of revisionist art history, one based on the peripheries of artistic production rather than on the perceived, or market-based, centre.’ Other digital archive projects and libraries, such as aaaarg, Memory of the World, Internet Archive, Samiz-Dat (formerly Dat Library), and Monoskop also reflect ‘recirculating archive’ projects, which make experimental, avant-garde and marginal cultural material public and freely available. These independent resources challenge traditional methodologies of archiving by recirculating riskier materials and affording new ways of engaging with these histories. They approach the archive—in the words of Sean Dockray and Benjamin Forster, founders of the peer-to-peer library project Samiz-Dat—‘not as a dead object of research but a set of possible tools waiting to be activated in new circumstances.’

Publications also utilise alternative methodologies to archive and recirculate culture outside of museological institutions. Archivio, 1:1:1 and Tinted Window, for instance, operate as revisionist projects that explore artistic and cultural histories through a serial publication framework. These independently-funded publications draw renewed attention to historical creative moments, figures and projects in the context of the present and emerging issues in contemporary culture. In these projects, the format of a publication provides critical ways of engaging with peripheral practices—those that tend to be more readily forgotten—and more creative ways of looking at these histories in the context of the present.

Fashion also has a history of alternative archives in the form of publications, exhibitions and databases. These projects engage with fashion history in more complex ways than brand and institutional efforts to archive fashion. Experimental and alternative archival strategies in fashion in particular have been productive in introducing new points of entry into fashion history.

An early example of an alternative archive of fashion is the Contemporary Fashion Archive (CFA), which operated between 2002 and 2007 as a multi-institutional project funded by the European Commission’s cultural program. The CFA created a digital archive that networked fashion designers with an ‘experimental and innovative approach to fashion.’ These designers, including Helmut Lang, Martin Margiela, Walter van Beirendonck, Raf Simons, Viktor & Rolf, Bless and Balenciaga, embodied unconventional approaches to fashion. The CFA was an ambitious project that was both an archive—containing catwalk images, fashion photographs, and ephemera—and a directory that functioned as a resource for collaboration. The platform fostered alternative models of practice (at the time) by archiving these works digitally and making them publicly available.

Publications also afford complex ways of engaging with archives. Certain recent publications, such as Monument and Mode and Mode (a publication I founded and edit), attempt to engage with archival materials in fashion, and its forgotten practitioners. Monument focuses on ‘Dutch wave’ designers at the end of the twentieth century, exploring one subject per issue in-depth. The publication thus becomes an archive of a distinctive period in Dutch design. Their first issue, which represented work from the archive of the Dutch designers Rozema/Teunissen, states that Monument aims to ‘bring these items back to the surface.’ The publication features original images of the work, an interview with the designers, written contribution and a fashion shoot restaging and recontextualising the original work. Similarly, Mode and Mode also forms an experimental archive through the collection of its issues, each of which looks at a marginal fashion publication as its subject. Producing an issue on their work—its issues have featured BLESS, Helen Hessel and Seth Shapiro—offers a way to bring renewed attention to evaluate it in relation to the present. For example, Mode and Mode often uses reprints of original publications, to make available and recirculate the work of these overlooked but experimental and critical projects. In both these contexts, a serial publication produces an accumulative, and unfolding archive in a way that is reflexive to its contents. In other words, the archive is not static; it evolves with the production of each issue.

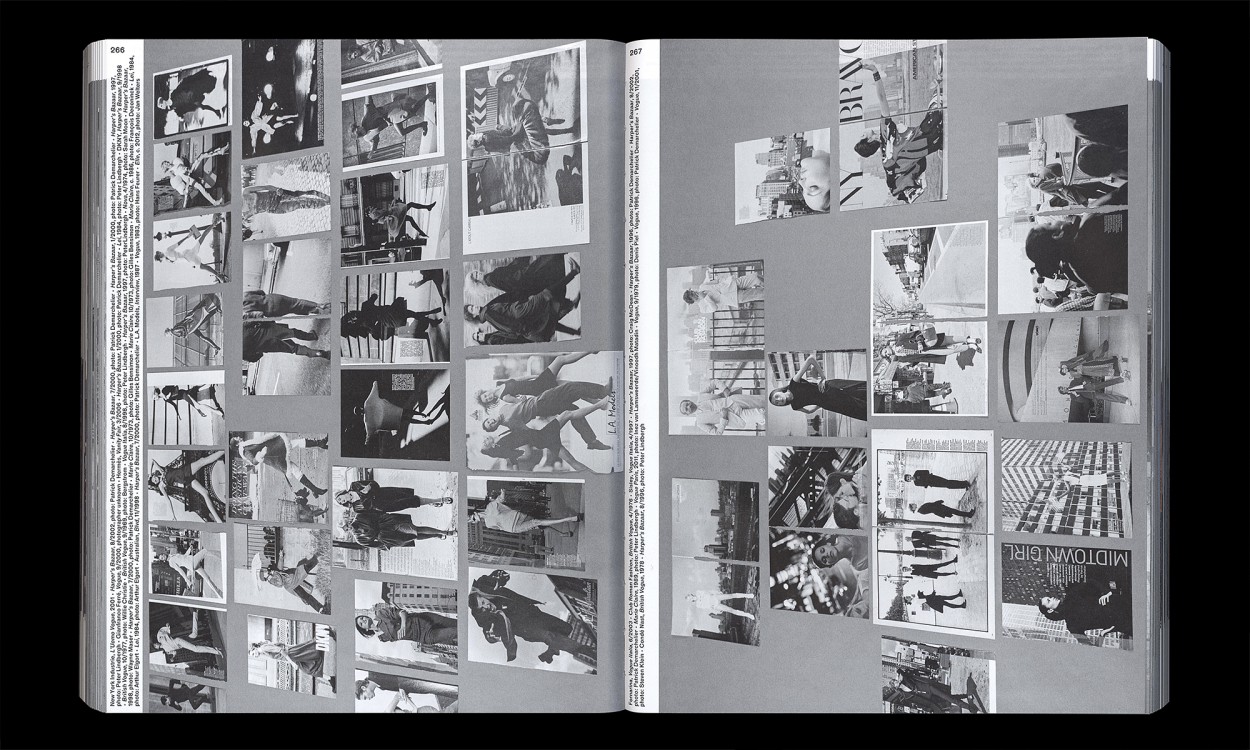

Another publication-archive in fashion is Joke Robaard’s Archive Species: Bodies, Habits, Practices. Since 1979, Robaard has amassed a vast collection of fashion images from magazines and printed matter in a physical experimental archive. Archive Species arranges this material into ‘dynamic series or cycles, generating new narratives and unexpected pathways of signification.’ Robaard’s archive of images suggests the ways in which an archive functions as a repository of material, one that can be activated in infinite ways by curating material into new arrangements, and thus new understandings, of the printed representation of fashion, particularly in fashion photography.

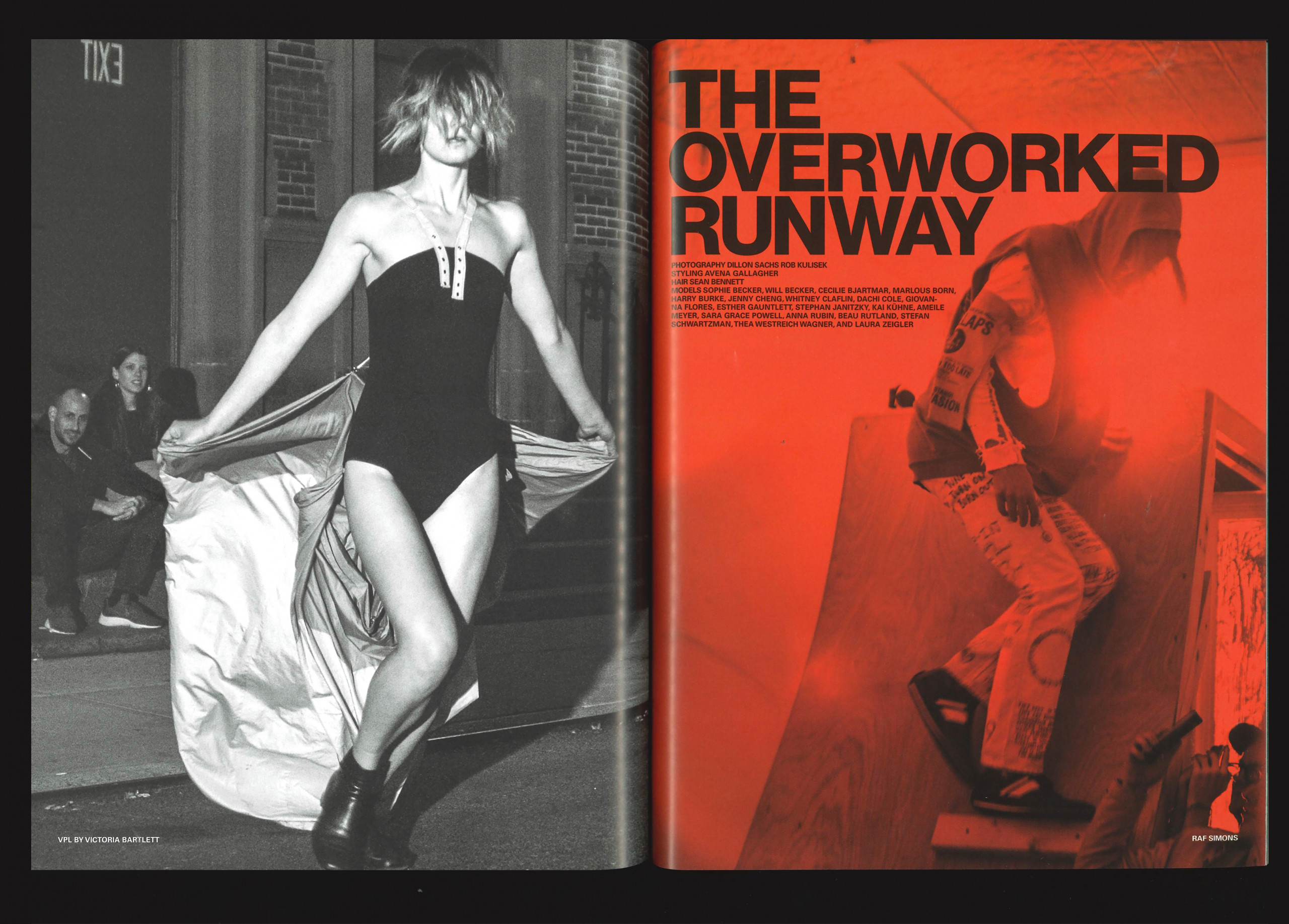

Exhibitions also offer interesting ways to reconfigure and represent archival fashion. An effort to experiment in this context is represented by curator Matthew Linde’s 2017 exhibition ‘The Overworked Body: An Anthology of 2000s Dress’ at Mathew Gallery in New York (and later became an edition of the magazine 299 792 458 m/s). The exhibition questioned the orthodoxies of how fashion is historicised and archived through a highly subjective, performative and experimental curatorial approach. The project focused on the recent history of early 2000s fashion as a transitional period ‘in an effort to obstruct our tendency to assign a specific style to a decade’ through a highly subjective curation of garments from experimental designers of the period. This was constructed in a gallery space through runway footage, designer publications and garments themselves, overlaid with experimental performances that re-enacted and interpreted aspects of the work. Curator Judith Clark is another example of a fashion curator and has become well-known for her unconventional curatorial approach. In her 2010 exhibition, ‘A Concise Dictionary of Dress’, she collaborated with psychoanalyst Adam Phillips to describe the exhibited garments not in terms of their material histories but in relation to anxiety, wish and desire. Presentational strategies such as these show that exhibitions about fashion history need not retell existing narratives of fashion history, but can be an opportunity to break these, and for new configurations and new ways of looking at the past in the intimate confines of an exhibition.

Fans collecting and sharing of archival fashion through blogging platforms like Blogspot and Tumblr (as well as forums) have formed fashion subcultures and sub-narratives for experimental and avant-garde fashion practices of the past. Shahan Assadourian turned his collecting of pre-digital fashion magazines, focusing on Japanese and Belgian designers, into an experimental Tumblr archive; Archivings.net. Archivings is a platform that reproduces the work of bygone fashion designers by republishing the runway collections of out-of-date print fashion magazines on the site. Each image is hand-scanned by Assadourian. The fan-site is now a substantial and valuable repository of digitised fashion, including many designers (such as the Japanese designer 20471120) that have otherwise largely been forgotten by fashion media in the shift to digital.

Recent digital platforms and dedicated archives of fashion’s printed matter Uncover and the International Library of Fashion Research (ILFR) also offer new approaches to archiving fashion. The IFLR is a physical as well as digital repository of printed matter in fashion, produced through substantial donations from designers, publishers and collectors. The library actively uses materials in its collection with an ongoing series of ‘curated collections’ and interpretative talks. Likewise, Uncover, the independent platform on which you read this article, provides a database of this lesser recognised material in fashion production. This allows printed matter, often considered secondary to garment production, to be critically explored (and activated) by students, practitioners, and researchers. More importantly, these platforms create fashion archives of experimental, peripheral materials and look at them through subjective, critical frames. These independent digital archives, publications and exhibition-based projects—produced autonomously from fashion’s market—critically engage with fashion’s past in the context of the present.

Archives are important; by preserving and displaying artefacts of the past, they produce knowledge in the present. In contrast to the archiving of fashion by institutions and brands—which favour fashion practitioners still active on the market—experimental fashion archives make accessible the riskier work of designers in fashion history, and some that, I would argue, are more interesting in their experimentality or resistance to commercial markets. In contrast to these dominant archival methods initiated by brands and institutions, experimental alternative archival projects like those discussed here represent new methods for archiving fashion and allow us to make our own configurations and discoveries of fashion history. We must have a variety of ways in which fashion is archived in order that we have a variety of ways to continue to use and learn from these histories.

[1] We have also seen, over the last few years, increased commodification of archival designer clothing through dedicated luxury resale platforms like RealReal, Heroine and Grailed, as well as marketplaces like Yahoo and eBay. These platforms offer a chance for individuals to buy and collect fashion (though often at significantly high cost) and form their own idiosyncratic archives.

[2] Sherman, L 2013, ‘For Brands Big and Small, Fashion Archives Can Be a Powerful Asset’ Business of Fashion. Access online: businessoffashion.com/articles/news-analysis/for-brands-big-and-small-fashion-archives-can-be-a-powerful-asset

[3] Chateigné, Y & Miessen, M 2016, ‘Introduction’, The Archive as a productive space of conflict, Sternberg, Berlin, p.11

[4] Ubuweb n.d., viewed 19 March 2021, ubu.com/resources/index.html.

[5] Dockray, S & Forster, B 2018, ‘README,md’, in D Blamey & B Haylock (eds), Distributed, Open Editions, London.

[6] Contemporary Fashion Archive, n.d., viewed 19 March 2021, unit-f.at/archive/unit-f/jart/prj3/unitf/main.html.

[7] The archive itself is no longer available as it ran into funding and copyright constraints in 2007.

[8] Berkulin, M 2018, ‘Editor’s Letter’, Monument, issue 1, p.3.

[9] Robaard, R & van Winkel, C 2019, Archive species: Bodies, habits, practices, Valiz, Amsterdam.

[10] Mathew Gallery 2017, ‘The overworked body: An anthology of 2000s dress’, viewed 19 March 2021,mathew-gal.de/Exhibitions/the-overworked-body/assets/MatthewLindepress.pdf.

They Look Of Reading,

We Look From Lacking

Pensive yet unaware, they are not here, but elsewhere; or so it seems. Disrupted but unoffended, they pause from absorption. — by Colby Vexler & Justin Clement

Experimental archives,

new fashion histories

The concept of the ‘archive’ seems to have captured once more the contemporary moment in fashion. — by Laura Gardner

From top to bottom

A header on a page is worn like a hat on the head. It is there as a part of a uniform that can indicate the wearers job, the books title and the stage of development in the narrative. — by Emma Singleton

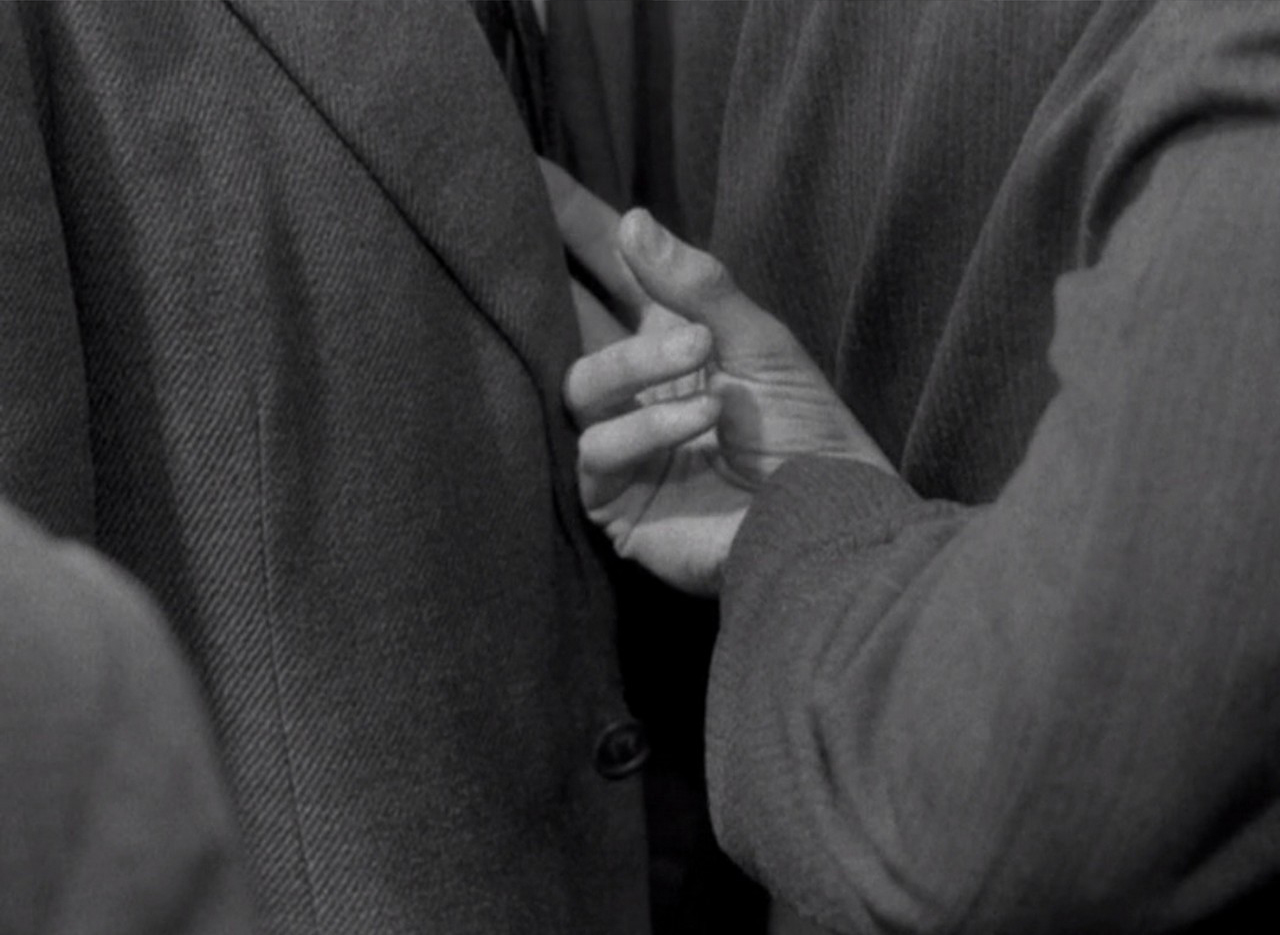

Her hand nuzzled

into his pocket

How the novel frees the garment of/from? fashion — by Femke de Vries

Keeping your heart in

a fabric padded pouch

Why do we wear our hearts on our sleeves? Why do we pad out our love as though its bound to hurt? Why does a heartbeat reverberate through the fabric of the skin? — by Emma Singleton