Features

In ‘Her hand nuzzled into his pocket’ Femke de Vries explores how the textual form of the garment in the novel leads to the possibility of inventing fictional garments. Switching between fiction and science-fiction she moves the reader in different realities in which the garment lives. The role of ‘textual clothing’ plays a big role within Femke’s work. As an artist / researcher she investigates the interaction between clothing as material utensils and fashion as a process of value production. Besides her own practice, Femke is also a co-founder of Warehouse.

Her hand nuzzled

into his pocket

There are various types of writing that revolve around or incorporate garments. The most obvious one is the fashion industries’ media. Besides that, we can think of historical costume books and instruction manuals for garment production, but a most interesting form of writing which often features garments, is the novel. The garment in the novel is a depiction of a garment that doesn’t have to be related to any real present, historical or future garment. Although the writer might have taken a real garment as inspiration, garments in novels can be purely textual.

Freedom through fiction

In The Fashion System Roland Barthes calls the text that describes a garment in a fashion magazine a ‘written garment,’ and explains that this written garment relates to a real, existing garment. Take for example captions that describe a real material garment as seen on a photo next to it. In the novel however, the ‘textual garment’ isn’t in service of a real garment (or image thereof). This disconnect from the materiality or visualization of a real garment in novels creates freedom and space for garments to take any (even fictional) kind of shape. [3] On a side note, the link to a material garment in fashion magazines doesn’t mean that these descriptions of garments are less fictional then the ones in a novel; the writings in fashion magazines use garments as a scaffolding to project dreams and emotions upon; values and meanings that are not inherently present in the garments’ materiality, and therefore artificially constructed or even made-up.

Garments in narratives

Although both employed for the building of (semi-)fictional stories there is a difference between the written garments in magazines and textual garments in novels. The main difference, as explained above, lies in the presence, or lack of a relation to a real garment. Secondly there is a difference in the type of narrative that these textual garments are employed to tell. The novel, as a form of literature, is known as having a lengthy narrative [4,5] and in many cases narrates individual experiences of characters (the exploration of inner feeling and thoughts), creating a closer more complex portrait of these characters and the world they live in, more so than in many other preceding forms of literature. [6] While the written garments in fashion magazines are part of short, fragmented narratives that revolve around trends and newness, all in order to sell, textual garments in novels, on the contrary, are anchored in a longer narrative, a storyline. As such I see novels as a place where garments are freed from materiality and the fashion industries’ alienated and fragmented narratives. They used as a tool for personal and cultural storytelling instead. A fundamentally different perspective on garments.

Fragmentary garments in new encounters

Although free from material and industrial fashion narratives, in the introduction of Clothing and Its Connotations in Postmodern American Fiction Theresa Wenzel stresses that textual garments in novels are considered valuable tools to characterize protagonists, and that this might be the reason why clothing has found its way into fiction. [7] This perspective on the garment, as a tool for the construction of identity, strongly overlaps with the role of the garment in fashion where they are known as tools that can construct and transform your performed identity regardless of your background, class, origins. A much-used situation for identity construction in novels is first encounters; the reader meeting the protagonist or the protagonist meeting another character etcetera. In such an encounter the character is shaped by describing a set of elements or characteristics of garments or accessories, that they’re supposedly wearing. In The Fashion System Roland Barthes writes that fashion magazines employ a form of, which I would say ‘selective writing,’ that presents a fragmentary garment; never describing the complete garment and only pointing out parts of a garment; a pocket, a belt, a brand name, the fit, the fabric. [8] And as such the magazine tells the reader what’s essential and what isn’t. In novels there is a similar form of fragmentary writing:

“As they walked down the control post, the jungle glowing two hundred yards away to their left, a large Chrysler with a dented fender swerved down the street and came to a halt in front of them. A tall man with blond hair, his double-breasted blue suit unbuttoned, climbed out.” [9]

“A car approached along the road. The driver signaled with the searchlight on the Land-Rover and the car turned and came to a halt beside them. A tall man wearing an army battledress over his civilian clothes jumped out.” [10]

Both examples describe the introduction of a new character coming from a car. The clothes, as well as the car, present us with a difference in identity and situation. A selection of elements is supposed to tell us something about the character: a double-breasted suit (formal?) but unbuttoned (informal?), civilian clothes but with an army battle dress over it (a quick change of clothes? Someone with several roles/identities?). However, as Theresa Wenzel also mentions in Clothing and Its Connotations in Postmodern American Fiction, garments are not only used to create an identity for a character, they are also used to create a ‘fictional world’ [11] and I believe we can add to that a sphere, setting, experience and even emotion:

“After the antiseptic odors and the atmosphere of illness and compromise with life, Louise’s brisk stride and fresh body seemed to come from a forgotten world. Her white skirt and blouse shone against the dust and the somber trees with their hidden audience”. [12]

“Still wearing the robe, she curls up between the sheets of a big white bed an prays from the wave to come, and take her for as long as it can.” [13]

Hands in pockets

In these examples the whiteness of the skirt and blouse (fresh, virgin), and the robe (either informal or formal wear), add to the creation of a sphere, of emotion.

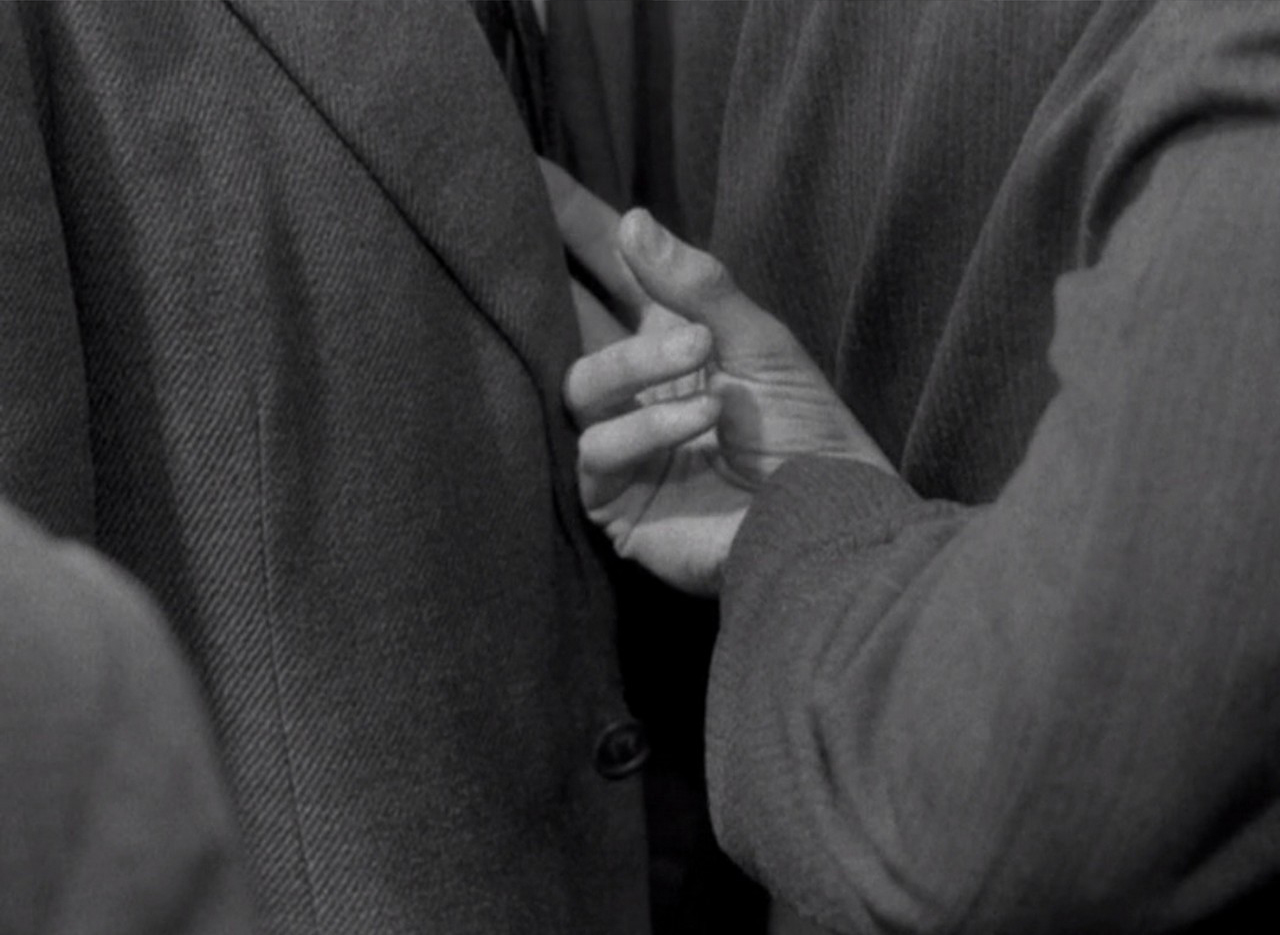

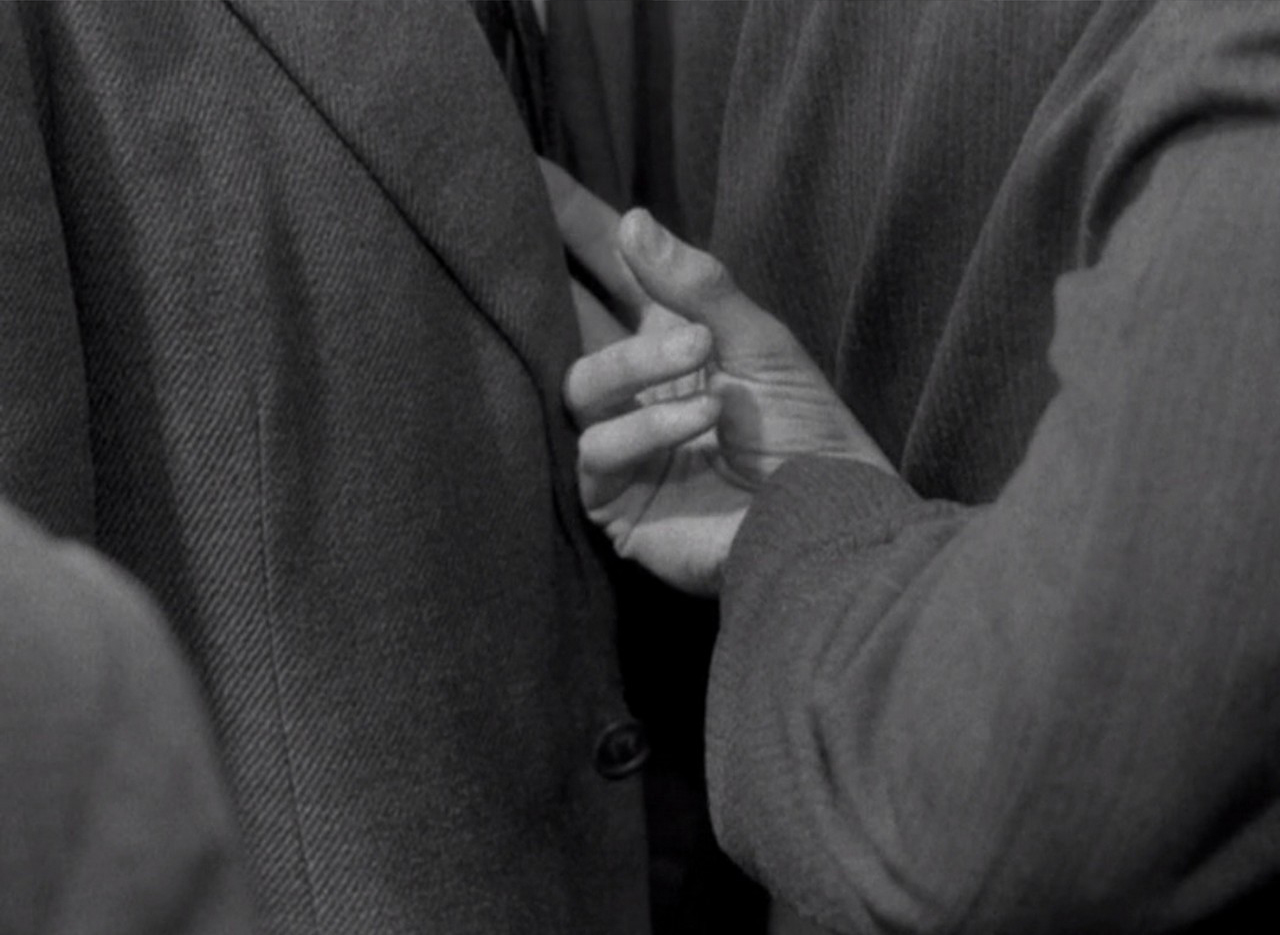

A garment, or rather element of a garment, that I often encounter in the depiction of emotions or sphere in novels, is the pocket. The power of the pocket in this ‘emotional/spherical storytelling lies in the character’s interactions with it; putting something in a pocket, taking it out, holding it there. But also, in the specific bodily interaction; one hand in the pocket is often used for nonchalance, both hands for ignorance or withdrawal. The way a hand is placed in a pocket tells a lot about the emotions of the character: “’Oh damn’, he exclaimed, plunging his hands into his pockets, patting them vainly for anything that would do. ‘Later,’ he told it”[14]. “Her hand nuzzled into his pocket”[15] and “He had bunched his fists in his trousers’ pockets, she recalled. ‘I think I shall love no one else, but I think you know that’”.[16] The pocket might just be a pocket, but there is a big difference between plunging, nuzzling or bunching a hand or fist in a pocket.

Pockets of emotion

At this moment I’m reading Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell and my eye is again caught by the role of pockets. The clothes featured in Nineteen Eighty-Four, a dystopian novel about a totalitarian surveillance state (trough cameras, microphones and two-way telescreens) in which history is denied and independent thinking repressed by the ‘thought police’ and ‘big brother’, are all familiar garments such as top-hats, overalls and aprons. The same goes for the pocket which in Nineteen Eighty-Four is strongly used to construct the identity of the characters, depict emotions, create a sphere and give insight into the regime. As such the story shows many ways to employ an element of a garment.

In the novel the pocket is strongly connected to contraband: the main character Winston, a party member that turns against the regime, risks his life when he visits a junkshop in a neighborhood of the proles. Affiliating with the proles and using time for something else than the party (having a ‘ownlife’) can get him arrested. In the junkshop he sees a glass paperweight with coral in it that makes him think of other times, before the present regime that erases all history.

“Winston immediately paid over the four dollars and slit the coveted thing into his pocket.” “It was very heavy in his pocket, but fortunately it didn’t make much of a bulge. It was a queer thing, even a compromising thing, for a party member to have in his possession.” [18]

Another situation that involves the pocket and forbidden goods is when Winston’s secret lover produces real chocolate she bought at the black market, from her pocket:

“Then, as though touching her waist had reminded her of something, she felt in the pocket of her overalls and produced a small slab of chocolate”. [19]

In Nineteen Eighty-Four the pocket is a private place that is able to ‘produce’ and hide contraband. This idea of the pocket as a place for hiding forbidden goods, fits within the general history of the pocket. Some Amish groups for example forbid clothing with (visible) pockets as pockets could be used to hold small items in secret that might lead to feelings of pride or individuality which can hurt the community as a whole. [20] For a long time, women’s clothes didn’t have pockets, only exterior pouches. Men’s clothes did have had pockets because they were allowed to own something (money, a wallet), clothes for women didn’t as they weren’t allowed to and were to depend on men. So, in the cultural history of clothes, the pocket is not just a place to practically carry something, it is a symbol of ownership, individuality, independence and privacy.

Emotions as contraband

Similar to that, in Nineteen Eighty-Four it’s clear that the real contraband is not the material, the glass paper weight or chocolate. As the regime that Winston lives in erases all history, these objects carry and create forbidden memories of previous times; dangerous thoughts, which are therefore being hidden in private pockets. Another contraband is love for anything else than the party which becomes evident in the part in which Winston’s secret girlfriend to - be, intentionally bumps into him in the hallway to slip a note into his hand which he transfers to his pocket. As it is impossible to read it out into the open; “he felt it with the tips of his fingers. It was a scrap of paper folded into a square.” [21] He unfolds it in his pocket considering to read it in one of the restrooms, but then we can read that there was no place where you could be more certain that the telescreens where watching continuously. [22] The note, he eventually finds out after tactically mixing it with work papers, reads “I Love You” [23] p.109.

The pocket space is therefore not only a space to keep forbidden material things but also memories and emotions. As such the pocket is the only place where emotions can be present. In this case it might concern written words on a note, but in many examples in novels the way a hand is put or behaves in a pocket is used to describe emotions: the angry or frustrated clenching fist or the warm and nuzzling hand. Emotions which are private, for one reason or another, hidden to other characters in the story. The precarity of privacy and emotions, which is an essential theme in the book, becomes evident when Winston takes a coin out of his pocket: “The tiny clear slogan of big brother was even on the twenty-five-cent piece he took out of his pocket”. [24] So big brother is also in his private emotional pocket space.

The pocket in itself is a symbol of privacy, pride, independency and individuality. The deployment of the pocket as a space for the expression of emotion, in a way strongly fits with the genre of the novel which mainly revolves around the narration of individual experience of characters, creating a close and complex portrait of the characters and context. More than in preceding forms of literature, the novel typically explores inner feelings and thoughts as well as complex and conflicting ideas and values. [25] In line with Nineteen Eighty-Four, we as readers, like big brother, are also in the pockets of the characters in these novels.

The reality effect in fiction

Reading this novel led me to think about garments in science fiction, a genre which, let’s say, combines the ‘real/familiar’ and the ‘unreal/unfamiliar’. Together with Fantasy, Science fiction is one of the most popular genres of novels, a genre which deals with speculative world building, often through technology. [26] The speculative and fictional character of the genre in combination with the freedom of the textual (non-material) garment is a combination that could actually truly set the garment free; in these unknown worlds and situations the garment could take any shape. However, (and although I’m still a beginning sci-fi reader, and now mostly read the classics, like Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Dispossessed by Ursula le Quinn, A Brave New World by Aldous Huxley), I haven’t encountered truly alternative fictional garments yet. Although it seems like a missed opportunity, there is something to gain from the familiar garment in the science fiction. In Dressed in Fiction Clair Hughes writes that “(…) references to dress for both reader and writer contribute to the ‘reality effect’.” [27] This ‘reality effect’, lends tangibility and visibility to character and context. With this concept she implies that she means ‘real garments’, garments that we are familiar with seeing and wearing. The ‘reality effect’ of the reference to familiar clothes in science fiction, can therefore add to the probability of speculative worlds and therefore helps us position ourselves in the narrative, subsequently leading to possible reflective perspectives on reality. So, the reality effect of familiar clothes, for example Winston’s pockets, can be a tool to assist us into the probability of the unknown, opening up to utopic and dystopic scenarios.

Fiction for reality

The reality effect of familiar garments in novels can possibly help us share- and connect to fictional stories that present us with alternative future perspectives. The way in which the novel frees the garment from the fashion industries’ fragmented narrative and the restrictions of materiality can help us to approach garments as personal and cultural objects that exist in longer storylines instead of fragmented alienating narratives aimed at commodification. As such we could maybe save the garment, and our relation with it, from the hands of the devouring fashion industry. Textual garments in novels could therefore assist us in the consideration of alternative future scenario’s that lie beyond the exploitative and polluting fashion industry.

[1] MURDOCH, I. (1963) The Unicorn. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, Ltd. p.41

[2] Ballard, J.G. (1966) The Crystal world. New York: Berkley Medallion Books. p.120

[3] Real clothing is burdened with practical considerations (protection, modesty, adornment); these finalities disappear from “represented” clothing, which no longer serves to protect, to cover, or to adorn, but at most to signify protection, modesty, or adornment (…); only written clothing has no practical or aesthetic function: it is entirely constituted with a view to signification: (…). Barthes, R. (1967). The Fashion System. Berkeley: University of California Press. p.8

[4] Prahl, A. (02/05/2019) What Is a Novel? Definition and Characteristics [Online] 02/05/2019. Available from: https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-a-novel-4685632 [Accessed: 18/03/2021]

[5] Of course, we can consider the fashion industry as one long narrative.

[6] Prahl, A. (02/05/2019) What Is a Novel? Definition and Characteristics [Online] 02/05/2019. Available from: https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-a-novel-4685632 [Accessed: 18/03/2021]

[7] Wenzel, T. (2007) Clothing and Its Connotations in Postmodern American Fiction. Göttingen: Grin.

[8] (…); the described garment is a fragmentary garment; in relation to the photograph, it is the result of a series of choices, of amputations; in the soft shetland dress with a belt worn high and with a rose stuck in it, we are told certain parts (….) and spared others (…), as if the women wearing this garment went about dressed only in a rose and softness. This is because, in fact, the limits of written clothing are no longer material limits, but limits in value (….). Applied to clothing, the order of language decides between the essential and the accessory; but it is a Spartan order: it relegates the accessory to the nothingness of the unnamed. Barthes, R. (1967). The Fashion System. Berkeley: University of California Press. p.15

[9] Ballard, J.G. (1966) The Crystal world. New York: Berkley Medallion Books. p.65

[10] Ballard, J.G. (1966) The Crystal world. New York: Berkley Medallion Books. p.108

[11] Wenzel, T. (2007) Clothing and Its Connotations in Postmodern American Fiction. Göttingen: Grin.

[12] Ballard, J.G. (1966) The Crystal world. New York: Berkley Medallion Books. p.120

[13] Gibson, W. (2004) Pattern Recognition. New York: Berkley Medallion Books

[14] LE CARRÉ, J. (1996) The Tailor of Panama. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p 362

[15] MURDOCH, I. (1963) The Unicorn. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, Ltd. p.41

[16] MIDDLETON, S. (1987) After a Fashion. London: Arrow Books Limited. p 78

[17] Orwell, G. (1949) Nineteen Eighty – Four. London: Secker & Warburg. P.95

[18] Orwell, G. (1949) Nineteen Eighty – Four. London: Secker & Warburg. P.96

[19] Orwell, G. (1949) Nineteen Eighty – Four. London: Secker & Warburg. P.123

[20] Cullen, M. Mennonites and Amish: 7 Common Questions [online] Available from: http://diversitythoughts.blogspot.com/p/mennonites-and-amish-7-common-questions.html. [Accessed: 18/03/2021]

[21] Orwell, G. (1949) Nineteen Eighty – Four. London: Secker & Warburg. P.108

[22] Orwell, G. (1949) Nineteen Eighty – Four. London: Secker & Warburg. P.108

[23] Orwell, G. (1949) Nineteen Eighty – Four. London: Secker & Warburg. P.109

[24] Orwell, G. (1949) Nineteen Eighty – Four. London: Secker & Warburg. P.27

[25] Gill, N.S.(10/05/2019)The Genre of Epic Literature and Poetry [Online] 10/05/2019. Available from: https://www.thoughtco.com/epic-literature-and-poetry-119651 [Accessed: 18/03/2021)]

[26] Prahl, A. (02/05/2019) What Is a Novel? Definition and Characteristics [Online] 02/05/2019. Available from: https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-a-novel-4685632 [Accessed: 18/03/2021]

[27] References to dress for both reader and writer contribute to the ‘reality effect’: they lend tangibility and visibility to character and context. From a sociological and historical viewpoint, it is worth our while to look closely at descriptions of dress in a novel, because dress is a visible aspect of history, a material index of social, moral an historical change which helps us understand and imagine historical difference (…). Hughes, C. (2006) Dressed in Fiction. New York: Berg. p.2

They Look Of Reading,

We Look From Lacking

Pensive yet unaware, they are not here, but elsewhere; or so it seems. Disrupted but unoffended, they pause from absorption. — by Colby Vexler & Justin Clement

Experimental archives,

new fashion histories

The concept of the ‘archive’ seems to have captured once more the contemporary moment in fashion. — by Laura Gardner

From top to bottom

A header on a page is worn like a hat on the head. It is there as a part of a uniform that can indicate the wearers job, the books title and the stage of development in the narrative. — by Emma Singleton

Her hand nuzzled

into his pocket

How the novel frees the garment of/from? fashion — by Femke de Vries

Keeping your heart in

a fabric padded pouch

Why do we wear our hearts on our sleeves? Why do we pad out our love as though its bound to hurt? Why does a heartbeat reverberate through the fabric of the skin? — by Emma Singleton